Unsinkable

Contrary to popular mythology, Titanic was never described as "unsinkable", without qualification, until after she sank. There are three trade publications (one of which was probably never published) that describe Titanic as unsinkable, prior to her sinking, but there is no evidence that the notion of Titanic's unsinkability had entered public consciousness until after the sinking.The first unqualified assertion of Titanic's unsinkability appears the day after the tragedy (on 16 April 1912) in The New York Times, which quotes Philip A. S. Franklin, vice president of the White Star Line as saying, when informed of the incident,

I thought her unsinkable and I based my opinion on the best expert advice available. I do not understand it.This comment was seized upon by the press and the idea that the White Star Line had previously declared Titanic to be unsinkable (without qualification) gained immediate and widespread currency.

David Sarnoff, wireless reports and the use of SOS

An often-quoted story that has been blurred between fact and fiction states that the first person to receive news of the sinking was David Sarnoff, who would later lead media giant RCA. In modified versions of this legend, Sarnoff was not the first to hear the news (though Sarnoff willingly promoted this notion), but he and others did staff the Marconi wireless station (telegraph) atop the Wanamaker Department Store in New York City, and for three days, relayed news of the disaster and names of survivors to people waiting outside. However, even this version lacks support in contemporary accounts. No newspapers of the time, for example, mention Sarnoff. Given the absence of primary evidence, the story of Sarnoff should be properly regarded as a legend.Despite popular belief, the sinking of Titanic was not the first time the internationally recognised Morse code distress signal "SOS" was used. The SOS signal was first proposed at the International Conference on Wireless Communication at Sea in Berlin in 1906. It was ratified by the international community in 1908 and had been in widespread use since then. The SOS signal was, however, rarely used by British wireless operators, who preferred the older CQD code. First Wireless Operator Jack Phillips began transmitting CQD until Second Wireless Operator Harold Bride half jokingly suggested, "Send SOS; it's the new call, and this may be your last chance to send it." Phillips then began to intersperse SOS with the traditional CQD call.

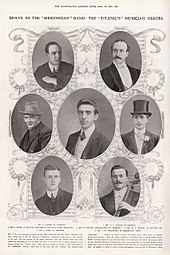

Titanic's band

One of the most famous stories of Titanic is of the ship's band. On 15 April the eight-member band, led by Wallace Hartley, had assembled in the first-class lounge in an effort to keep passengers calm and upbeat. Later they moved on to the forward half of the boat deck. The band continued playing, even when it became apparent the ship was going to sink, and all members perished.There has been much speculation about what their last song was. A first-class Canadian passenger, Mrs. Vera Dick, alleged that the final song played was the hymn "Nearer, My God, to Thee". Hartley reportedly once said to a friend if he were on a sinking ship, "Nearer, My God, to Thee" would be one of the songs he would play. But Walter Lord's book A Night to Remember popularised wireless operator Harold Bride's 1912 account (New York Times) that he heard the song "Autumn" before the ship sank. It is considered Bride either meant the hymn called "Autumn" or waltz "Songe d'Automne" but neither were in the White Star Line songbook for the band. Bride is the only witness who was close enough to the band, as he floated off the deck before the ship went down, to be considered reliable—Mrs. Dick had left by lifeboat an hour and 20 minutes earlier and could not possibly have heard the band's final moments. The notion that the band played "Nearer, My God, to Thee" as a swan song is possibly a myth originating from the wrecking of SS Valencia, which had received wide press coverage in Canada in 1906 and so may have influenced Mrs. Dick's recollection. Also, there are two, very different, musical settings for "Nearer, My God, to Thee": one is popular in Britain, and the other is popular in the U.S., and the British melody might sound like the other hymn ("Autumn"). The film A Night to Remember (1958) uses the British setting; while the 1953 film Titanic, with Clifton Webb, uses the American setting.

The stories of W.T. Stead

Main article: William Thomas Stead

Another often cited Titanic legend concerns perished first class passenger, William Thomas Stead. According to this folklore, Stead had, through precognitive insight, foreseen his own death on Titanic. This is apparently suggested in two fictional sinking stories, which he penned decades earlier. The first, "How the Mail Steamer Went Down in Mid-Atlantic, by a Survivor" (1886), tells of a mail steamer's collision with another ship, resulting in high loss of life due to lack of lifeboats. The second, "From the Old World to the New" (1892) features a White Star Line vessel, Majestic, that rescues survivors of another ship that had collided with an iceberg.The Titanic curse

When Titanic sank, claims were made that a curse existed on the ship. The press quickly linked the "Titanic curse" with the White Star Line practice of not christening their ships (notwithstanding the opening scene of the film A Night to Remember).One of the most widely spread legends linked directly into the sectarianism of the city of Belfast, where the ship was built. It was suggested that the ship was given the number 390904 which, when reflected, resembles the letters "NOPOPE", a sectarian slogan attacking Roman Catholics, widely used by extreme Protestants in Northern Ireland, where the ship was built. In the extreme sectarianism of the region, the ship's sinking was alleged to be on account of anti-Catholicism by her manufacturers, the Harland and Wolff company, which had an almost exclusively Protestant workforce and an alleged record of hostility towards Catholics. (Harland and Wolff did have a record of hiring few Catholics; whether that was through policy or because the company's shipyard in Belfast's bay was located in almost exclusively Protestant East Belfast—through which few Catholics would travel—or a mixture of both, is a matter of dispute.) In fact, RMS Olympic and Titanic were assigned the yard numbers 400 and 401 respectively.